We developed a broad range of probabilistic modelling tools for the design and analysis of biological experiments as well as clinical data

Decoding and optimizing nerve signalling

At IOS Health we focus on neural signalling in the vagus nerve. Systematic bioelectronic stimulation of the vagus nerve can have drastic physiological effects. Careful modelling of the response by Gaussian processes and Bayesian optimization enables us to hone in on a desired effect quickly and efficiently Wernisch et al., 2024, (pdf, also this talk at Bayes4Health2021). The complex relationship between various nerve fibre stimulations and physiological effects is explored in Berthon et al., 2023. Decoding signals in whole nerve recordings is a challenging task which we approach with a variety of statistical and ML methods.

Evidence synthesis

There is growing interest in analysing large heterogeneous data sets jointly, that provide different views on common underlying features. We have recently proposed a principled framework to merge separate Bayesian models, each tailored to a specific data set, into one model through common parameters (Goudie, Presanis, Lund, De Angelis, Wernisch, 2018). A key requirement is the ability to estimate densities. We are exploring the potential of deep learning approaches, such as normalising flows, to provide detailed density estimates even for sparse data in high dimensions and the integration of such estimations into Monte Carlo sampling from or variational optimisation of Bayesian models. Another aspect of integrating heterogeneous data is the restriction of the flow of information through a so called ‘cut’ in a Bayesian model. There has been much debate about its meaning and we are developing a principled framework for such operator based on variational inference. The ability to estimate densities reliably plays a key role in this approach.

Design of experiments through active learning

Experimental Python package dynlearn

Controlled differentiation of stem cells is driven by careful administration of stimulating factors to cell cultures. The exact amount and timing of such stimulation is largely a matter of trial and error. We propose a Reinforcement Learning framework implemented in Tensorflow to optimise such dynamic experiments. Since, unlike the typical situation for many RL tasks, the number of possible experiments is extremely limited, modelling of the dynamics through Gaussian process state space models (instead of a vanilla neural networks) is crucial. In simulations of realistic systems we achieve remarkable optimisation results with only a limited number of experiments. Some details can be found in this talk at Costnet18. Some earlier work on active learning for gene networks is described in Pournara and Wernisch, 2004.

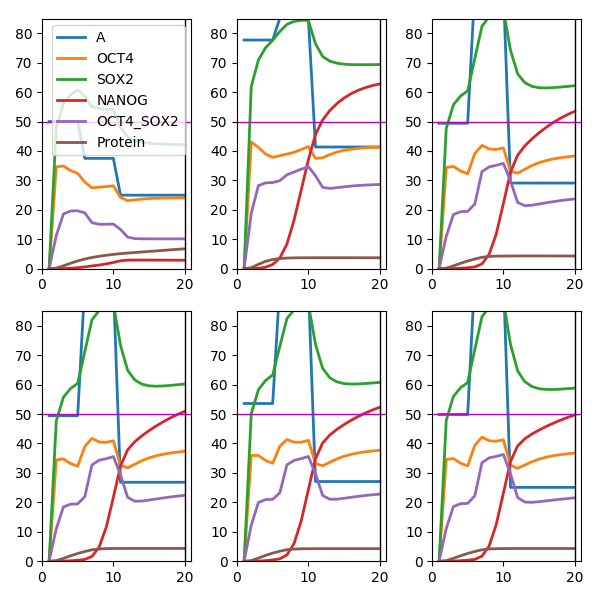

An example shows how NANOG production (red line) for a Biomodel Chickarmane2006 - Stem cell switch reversible can be pushed to a level of 50 at time 10 with a series of repeated experiments (provided by the Tellurium simulator as a black box). The algorithm proposes a new input A (blue line) each round to explore and optimise the (unkwnown) dynamics of the system as reconstructed by Gaussian processes.

Prediction in intensive care

With the increasing availability of health care data, including measurements of biomarkers, there is growing interest in the prediction and the understanding of adverse events such as a secondary infection of patients in intensive care. Modeling of trajectories as well as the dynamics through Gaussian processes is a promising route that we apply to the prediction of secondary infections as well as the long-term effect of traumatic brain injury. A key step is the understanding of the causal relationship of components of the immune response. We explore how far concepts of NLTSA (non-linear time series analysis) such as convergent cross mapping (Sugihara et al. 2012) can be put on a firm probabilistic basis and used for this purpose. For some details on this type of approaches see a Tutorial on ML for ICU data.

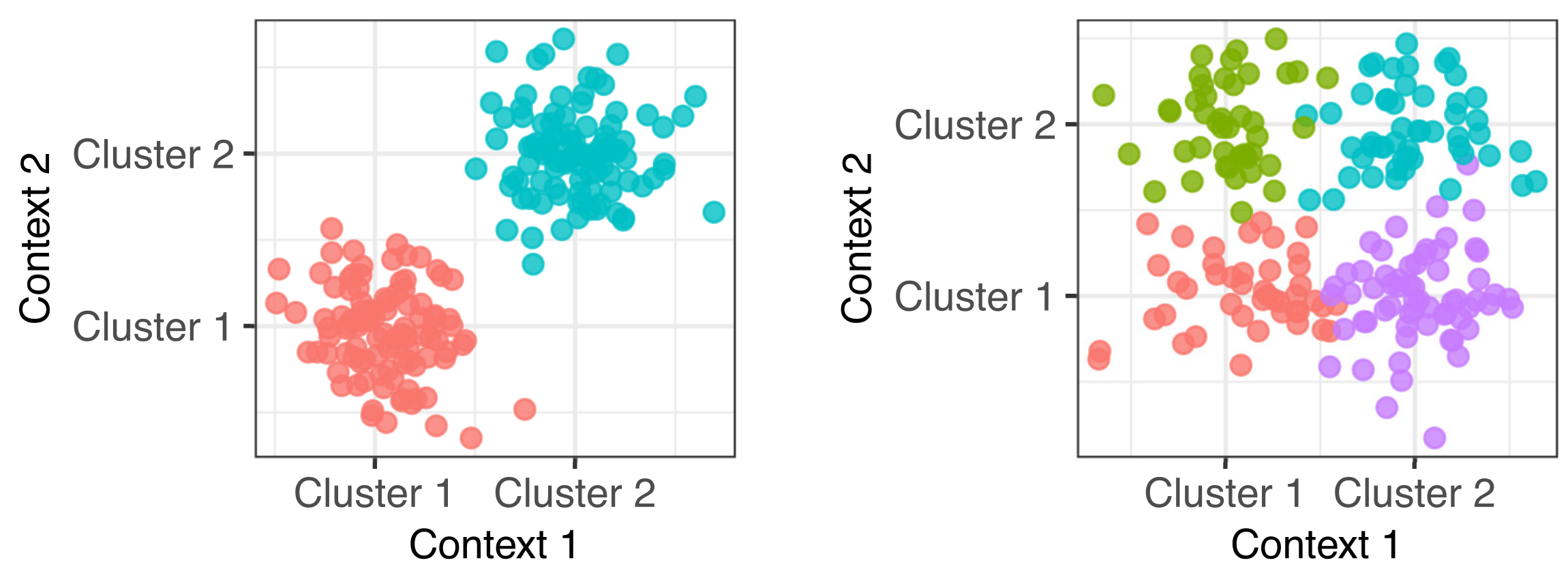

Clusternomics: integrative clustering

In genomics we frequently have information about our samples of interest from many different contexts. For example in cancer genomics, we may have gene expression, DNA methylation, micro-RNA expression and copy number variation measurements. Integrative clustering combines data from multiple contexts and suggests one overall clustering that is shared across all the contexts. Most integrative clustering models assume there is one overall clustering shared amongst the contexts and any deviations from this are more-or-less random noise. We explored the idea that there may be more complex relationships between the clusters in each context (Gabasova, Reid and Wernisch, 2017).

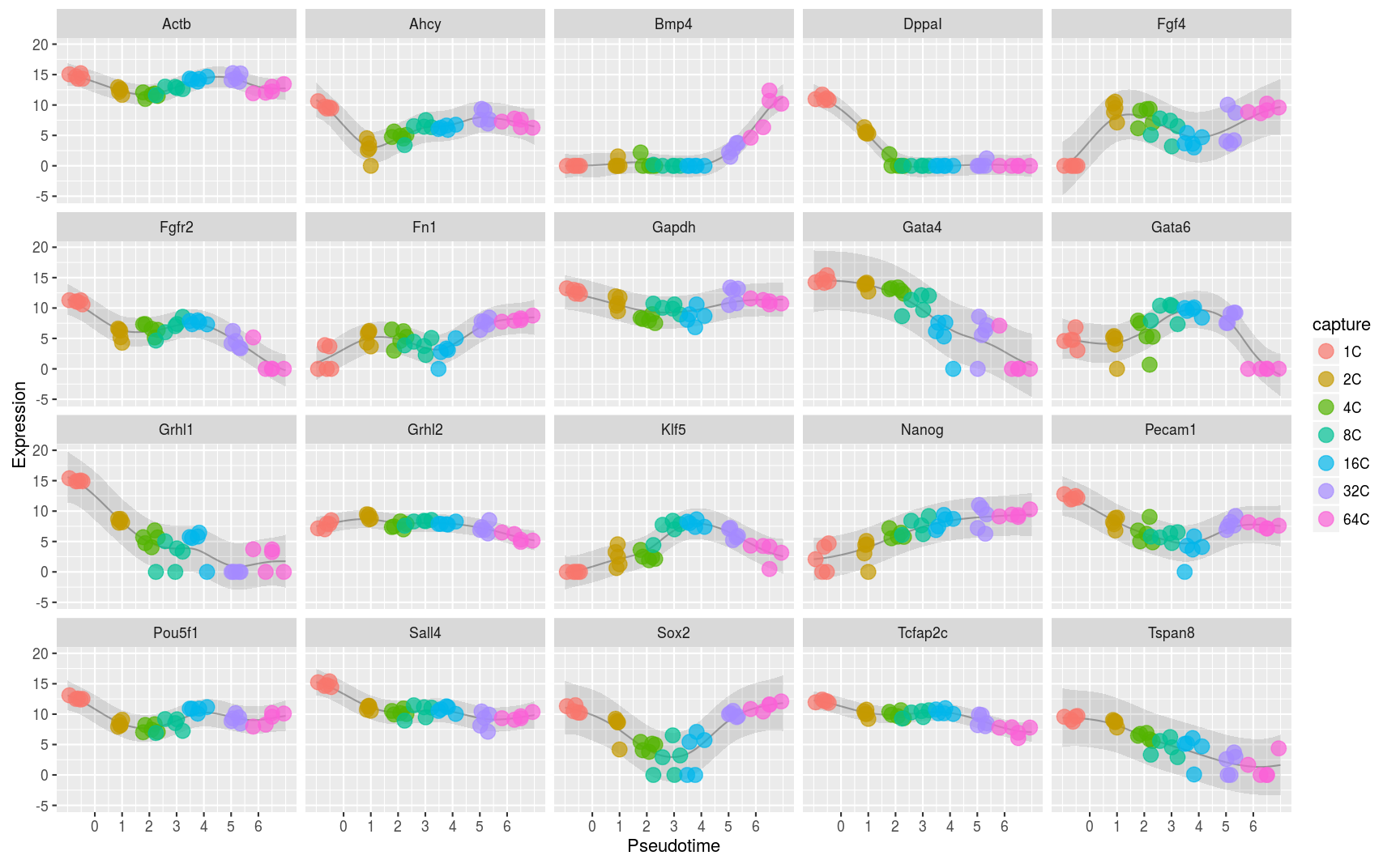

Ordering single cells in pseudotime

Many single cell experiments take samples at a handful of time points within a biological process. Unfortunately individual cells may progress through the process at different rates and this can confound any analysis of the data. In this project we modelled this effect using a latent variable Gaussian process model and inferred latent pseudotime variables to place each cell on a trajectory within the process. Downstream analyses of the data are more effective when these pseudotimes are estimated well (Reid and Wernisch,2016 and Strauss, Reid, and Wernisch, 2018).

Inferring gene regulatory relationships from matched copy number and transcriptomics data sets

Cancer cells often show large scale disruptions of their genomic arrangements with some parts of the genome multiplied and others deleted. This provides a natural randomisation experiment that can be exploited to infer gene regulatory relationships. By regulatory rela-Newton and Wernisch tionship we mean either a direct relationship, of a transcription factor on its target gene, or a very indirect one, through a pathway containing intermediate regulatory steps. We have trawled multiple datasets to analyse them for correlation patterns that are telltale signs of regulation (Newton and Wernisch, 2014, 2015, manuscript 2018). We published the database METAMATCHED, comprising the results from such an analysis of a large number of publically available cancer dataset.